Chapter 17 Using regression diagnostics

17.1 Introduction

In the last chapter we learnt how to carry out regression diagnostics. Fortunately we don’t have to do all of that work each time we fit a model. R has a built in facility to make these plots for us. In this chapter we’ll walk through how to use this with regression and one-way ANOVA models.

17.2 Diagnostics for regression

We’ll use the glucose release example from the [Simple regression in R] chapter to step through the easy way to make diagnostic plots.

Walk through example

You should work through the example in the next few sections.

You’ll need to read in the GLUCOSE.CSV file again and fit the regression using the lm function as before.

The built in facility for diagnostic plots in R works via a function called plot. For example, to produce a residuals vs fitted values plot, we use:

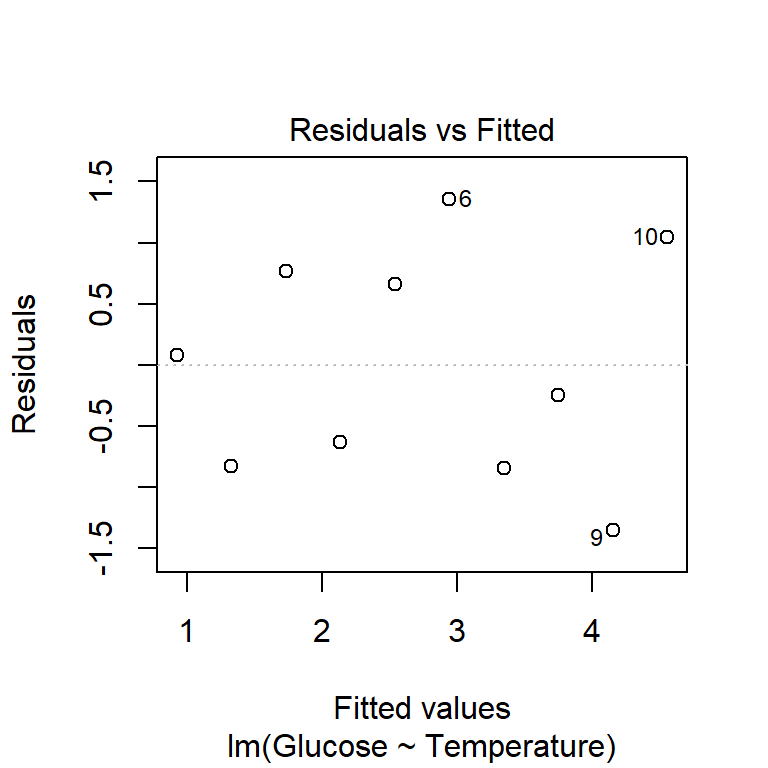

The first argument is the name of fitted model object. The second argument controls the output of the plot function: which = 1 argument tells it to produce a residuals vs. fitted values plot. The add.smooth = FALSE is telling the function not to add a line called a ‘loess smooth’. This line is supposed to help us pick out patterns, but it tends to over fit the relationship and leads people to see problems that aren’t there. If we can’t see a clear pattern without the line, it probably isn’t there, so it’s better not to include it at all.

Remember that this plot allows us to evaluate the linearity assumption. Here, we’re looking for any evidence of a systematic trend (e.g. a hump or U-shaped curve) here. As there’s no obvious pattern we can accept the linearity assumption and move on to the normality assumption.

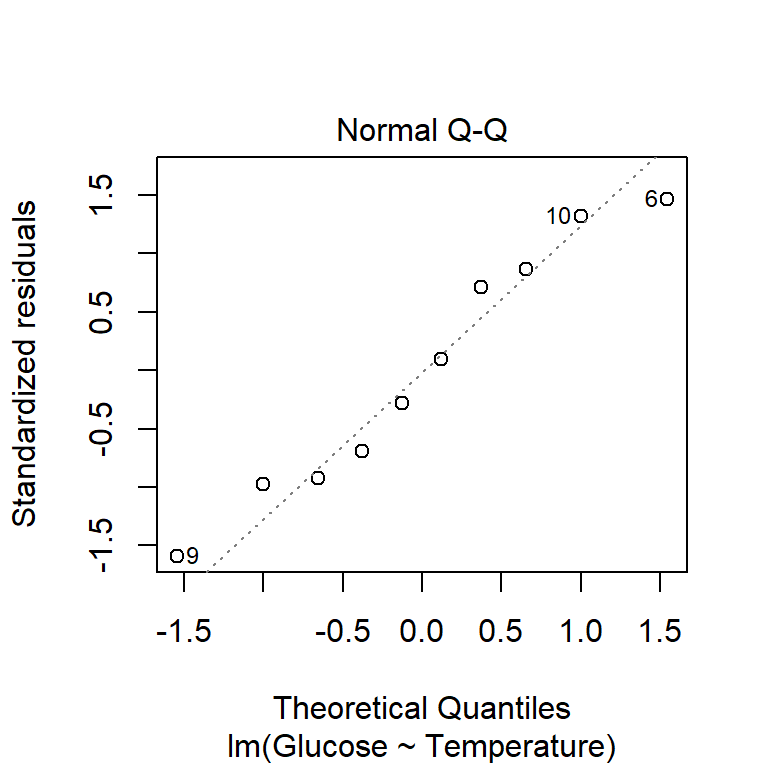

We use the plot function to plot a normal probability diagnostic by setting which = 2:

This produces essentially the same kind of normal probability plot we made in the previous chapter, with one small difference. Rather than drawing a 1:1 line, the ‘plot’ function shows us a line of best fit. This just allows us to pick out the curvature a little more easily. There’s nothing here to make us worry about this assumption - the points are close to the line with no systematic trend away from it.

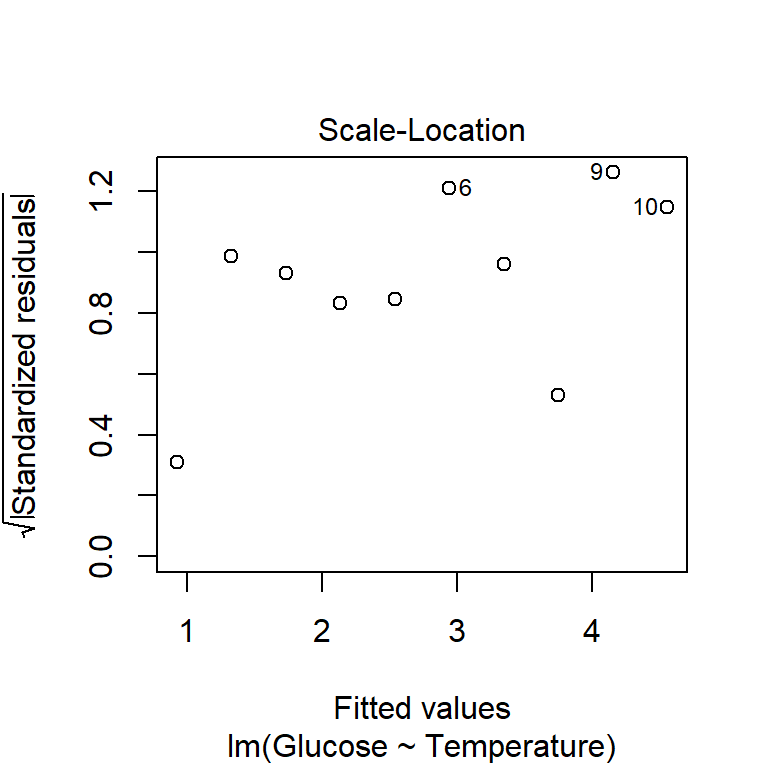

Finally, we can produce a scale-location diagnostic plot using the plot function to assess the constant variance assumption. Here we use which = 3 and again we suppress the line (using add.smooth = FALSE) to avoid finding spurious patterns:

Remember in this plot we’re looking for any sign of the size of the transformed residuals either increasing or decreasing as the fitted values get larger. This plot looks good - as the relationship here looks pretty flat we can conclude that the variability in the residuals is constant.

Don’t panic if your diagnostics aren’t perfect!

The good news about regression is that it is quite a robust technique. It will often give us reasonable answers even when the assumptions are not perfectly fulfilled. We should be aware of the assumptions but should not become too obsessed by them. If the violations are modest, it is often fine to proceed. We just need to interpret results with care. Of course, we have to know what constitutes a ‘modest’ violation. There are no hard and fast rules. The ability to make that judgement is something that comes with experience.

17.3 Diagnostics for one-way ANOVA

The term ‘regression diagnostic’ is a bit of a misnomer. A more accurate term might be ‘linear model diagnostic’ but no one really uses this. Regression diagnostics can be used with many different kinds of models. In fact, the diagnostic plots we have introduced above can be applied to any model fitted by the lm function, including ANOVA models.

Walk through example

You should work through the example in the next few sections.

Let’s step through the diagnostics for a one way ANOVA now, using the corncrake hatchlings example from the [One-way ANOVA in R] chapter. Read the data into R again and fit the model as before.

The first diagnostic plot we produced for the regression model above is the residuals vs. fitted values plot. In a regression this is used to evaluate the linearity assumption. What does it do in a one-way ANOVA? Not much of use to be honest. There isn’t much point making a residuals vs. fitted values plot for a one-way ANOVA. Why? Because the residuals will never show a trend with respect to the ‘fitted values’, which are just the group-specific means. That’s one thing less to worry about.

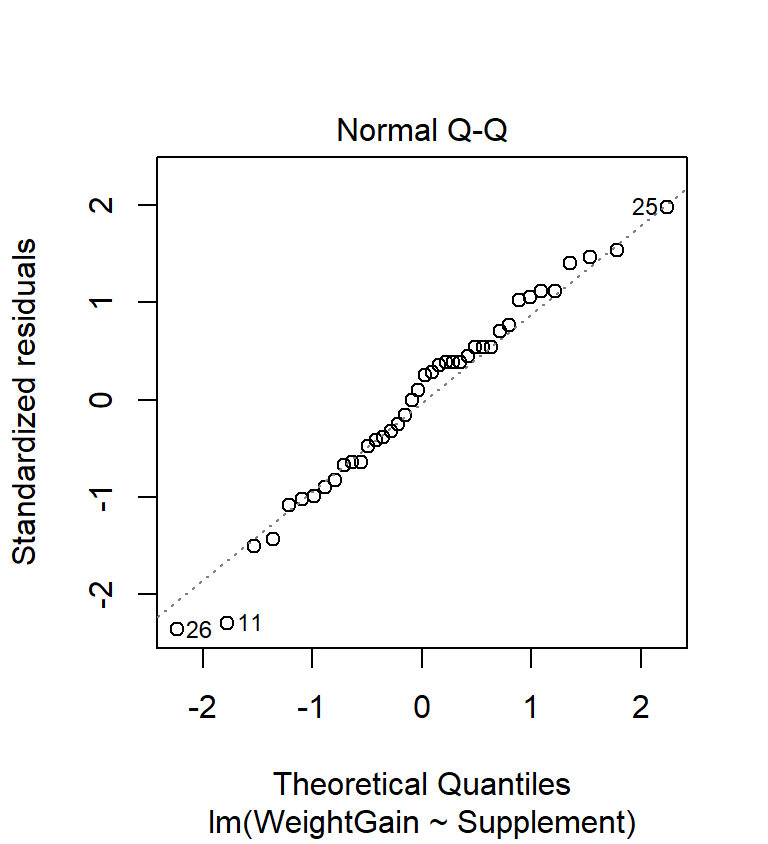

The normal probability plot is used to identify departures from normality. This plot allows us to check whether the deviations from the group means (the residuals) are likely to have been drawn from a normal distribution. Here’s the normal probability plot for our example:

This looks very good. The points don’t deviate from the line in a systematic way (except for a couple at the lower end—this is nothing to worry about) so it looks like the normality assumption is satisfied.

This looks very good. The points don’t deviate from the line in a systematic way (except for a couple at the lower end—this is nothing to worry about) so it looks like the normality assumption is satisfied.

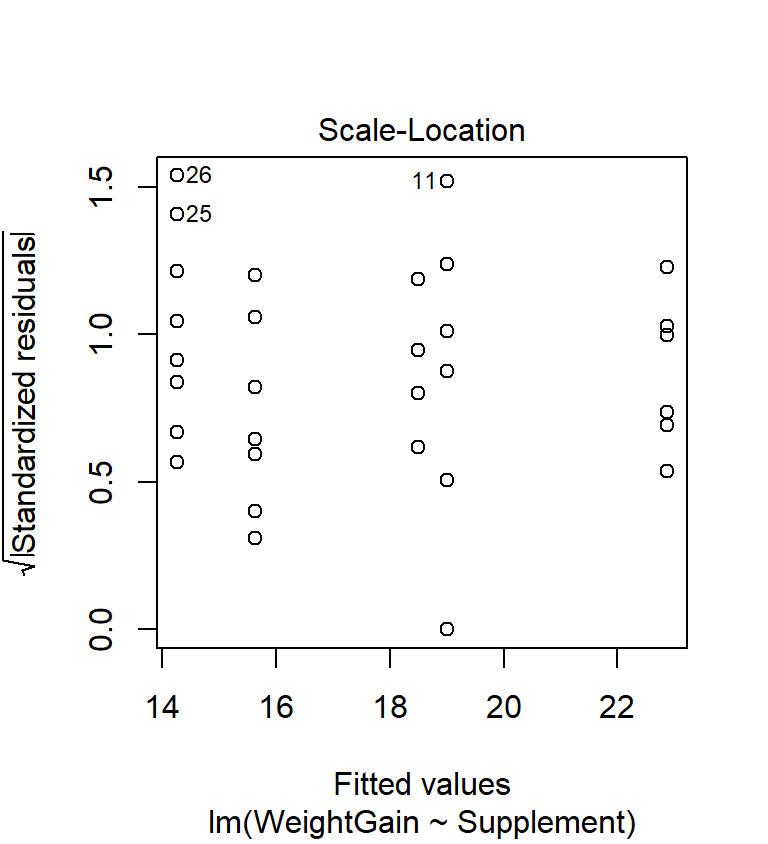

The scale-location plot allows us to evaluate the constant variance assumption. This allows us to see whether or not the variability of the residuals is roughly constant within each group. Here’s the scale-location plot for the corn crake example:

The warning sign we’re looking for here is a systematic pattern. We want to see if the magnitude of the residuals tends to increase or decrease with the fitted values. If such a pattern is apparent then it suggests that variance changes with the mean. There is no such pattern in the above plot so it looks like the constant variance assumption is satisfied.

17.3.1 Aside: formal test of equality of variance

It is not critical that you learn the material in this short section. It is provided so that you know how to test for equality of variance. You won’t be asked to do this in an assessment.

Looking back over the scale-location plot, it seems like three of the treatment groups exhibit similar variability, while the remaining two are more variable. They aren’t wildly different, so it is reasonable to assume the differences are due to sampling variation. People are sometimes uncomfortable using this sort of visual assessment. They want to see a p-value… A number of statistical tests have been designed to evaluate the equality of variance assumption. The most widely used is the Bartlett test (the bartlett.test function in R). Here is how to use it:

##

## Bartlett test of homogeneity of variances

##

## data: WeightGain by Supplement

## Bartlett's K-squared = 3.6444, df = 4, p-value = 0.4563This looks just like the t-test specification. We use a ‘formula’ (WeightGain ~ Supplement) to specify the response variable (WeightGain) and the grouping variable (Supplement), and use the data argument to tell the bartlett.test function where to look for these variables. The null hypothesis of a Bartlett test is that the variances are equal, so a non-significant p-value (>0.05) indicates that the data are consistent with the equal variance assumption. That’s what we find here.

Generally speaking, we don’t recommend that you carry out a statistical test to evaluate the equality of variance assumption. We have shown it because some people seem to think they are needed. Here is why we think they are wrong: formal tests of equality of variance are not very powerful (in the statistical sense). This means that in order to detect a difference, we either need a lot of data, or the differences need to be so large that they would be easy to spot using a graphical approach.