Chapter 5 Learning from data

Statistics is the science of learning from data, and of measuring, controlling, and communicating uncertainty; and it thereby provides the navigation essential for controlling the course of scientific and societal advances

The particular flavour of statistics covered in this book is called ‘frequentist statistics’. In one sense, it isn’t very important that we realise this. From a practical perspective, it’s possible to apply frequentist tools by just learning a few basic ‘rules’. Nonetheless, it is helpful to acquire a rough sense of how frequentist ideas work so that these rules can be applied correctly. Ultimately, it’s much easier to use statistical tools if we understand (at least roughly) how they work.

The goal of the next few chapters is to provide an overview of the important ideas. We’re not going to cover the challenging mathematical details in any great detail. Instead, we just want to get a conceptual feel for the most important ideas. These can be difficult to understand at first. This is fine. We’ll return to them repeatedly as we introduce different statistical models and tests.

We’re going to start, in this chapter, by laying out a somewhat simplified overview of the steps involved in ‘doing frequentist statistics’. We’ll also introduce a few key ideas and definitions along the way. Later chapters will drill down into the really important ideas—things like sampling variation, standard errors, null hypotheses and p-values. These are the concepts we really need to understand.

5.1 Populations

When a biologist talks about a population they mean a group of individuals of the same species who interbreed. This definition should be familiar to you. But what does a statistician mean when they talk about populations? The word has a different meaning in statistics. It is a much more abstract concept: a statistical population is any group of items that share certain attributes or properties. This is best understood by example…

The readers of this book could be viewed as a statistical population. APS students have a common interest in biology, they are mostly in their late teens and early 20s, and they tend to have similar educational backgrounds and career aspirations. As a consequence of these similarities, APS students tend to be more similar to one another than they would be to a randomly chosen inhabitant of the UK.

The different areas of peatland in the UK comprise a statistical population. There are many peatland sites in the UK, and although their ecology varies somewhat from one location to the next they are also very similar in many respects. Peatland habitat is generally characterised by low-growing vegetation and acidic soils. If you visit two different peatland sites in the UK, they will seem quite similar compared to, for example, a neighbouring calcareous grassland (think of the Peak District).

A population of plants or animals (as understood by biologists) can obviously be thought of as a statistical population. Indeed, this is often the kind of population a biologist is interested in. The individuals that comprise a biological population share common behaviours, physiology and life history characteristics. Much of organismal biology is concerned with learning about these properties of organisms.

Populations are conceptualised as fixed but unknown entities within the framework of frequentist statistics. The goal of statistics is to learn something about populations by analysing data collected from them.

It is important to realise that ‘the population’ is defined by the investigator, and the ‘something we want to learn about’ can be anything we know how to measure. Consider the examples again. A social scientist might be interested in understanding the political attitudes of undergraduates, so they might choose to survey a group of students in their university. A climate change scientist might measure the mass of carbon that is stored in peatland areas at sites across Scotland and northern England. A behavioural ecologist might want to understand how much time beavers spend foraging for food, so they might study one of the two Scottish populations.

Let’s review the steps involved in these kinds of studies.

5.2 Learning about populations

The examples discussed above involve very different kinds of populations and questions. Nonetheless, there are fundamental commonalities in how these questions are addressed. The process can be broken down into a number of distinct steps:

Step 1: Refine your questions, hypotheses and predictions

This step was discussed in [The scientific process] chapter. The key point is that we should never begin collecting data until we’ve set out the relevant questions, hypotheses and predictions. This might seem very obvious, but it is surprising how often people don’t get these things straight before diving into data collection. Collecting data without a clear scientific objective and rationale is guaranteed to waste time and energy.

Step 2: Decide which population(s) is (are) important

The second step is to decide which population (or populations) we should study. This problem is more subtle than it first appears. What constitutes ‘the population’ might be fairly obvious in some kinds of study. In each of the three cases considered above, the corresponding populations we choose to study could be undergraduate students in APS, peatland habitats from across the UK, and beavers in Scotland, respectively. Each of these is an example of what is called an observational study. It is often fairly easy to define what we mean by a population in this kind of study (though that doesn’t mean the population is easy to study—we’ll return to this idea later).

What happens if we’re planning an experiment? Imagine that we want to test a prediction that nutrient addition reduces biodiversity in chalk grasslands. We might set up an experiment with two kinds of plots: 1) manipulated plots where we add fertiliser, and 2) control plots where we do nothing. Comparing these would allow us to assess the impact of adding nutrients. There are two statistical populations in this setting: control and manipulated communities. These two populations are completely defined by the experimental design. The nutrient addition plots don’t exist until we do the experiment. The weird mental contortion that a frequentist does is to imagine that the experimental plots are part of some larger, unobserved population of nutrient addition plots.

Again, the important point is that statistical populations are something the investigator defines. They might be ‘real’, like the undergraduates in APS, or they might be something that doesn’t really exist in a meaningful way, like a population of not-yet-realised experimentally manipulated plots. In either case, we can use the same statistical techniques to learn about ‘the populations’.

Step 3: Decide which variables to study

The next step is to decide which features of the population we need to measure to address our question. This comes down to deciding which variable (or variables) we need to measure. In the examples above, the appropriate variables might be things like a standardised measure of political attitude, the mass of carbon stored per unit area, or the body mass of individuals in the biological population.

This step is often reasonably straightforward, though some effort may be required to pick among different options. There isn’t a whole lot of ambiguity associated with a physical variable like body mass, but something like ‘political attitude’ needs careful thought. Can we quantify this by studying just one thing, like voting patterns? Probably not.

Part of the art of designing a good data collection protocol is deciding what to measure. We discussed some of the considerations in the [Data and variables] chapter. What matters most is that we choose the right kind of variables to address the substantive research question.

Step 4: Decide which population parameters are relevant

Once we have decided which variables to study, we have to decide which population parameter is relevant. A population parameter is a numeric quantity that describes a particular aspect of the variables in the populations (to be more precise, it describes a feature of the distribution of the variables in the population).

A simple population parameter that many people are familiar with is the population mean. We often study means because they allows us to answer questions like, “how much, on average, of something is present?”. Much of this book is about asking questions of population means, though other population parameters may also be important, e.g.

The goal of statistical genetics is to partition variability among individuals—we want to know how much phenotypic variation is due to genetic vs. non-genetic sources. In this case it is population variances we want to learn about.

Sometimes we want to understand how two or more aspects of the population are related to one another. In this situation a correlation coefficient might be the right population parameter to focus on.

Step 5: Gather a representative sample

If we could measure every object in a population we wouldn’t need to use statistics. We’d simply calculate the quantity of interest using an exhaustive sample. Of course, in the real world we have limited time and money to invest in a problem, no matter how important it is. This means we have to work with a sample of a population.

A sample is just a subset of the wider population that has been chosen so that it is representative of that population. The word ‘representative’ in that statement is very important. If we can’t collect a representative sample it is very difficult to infer anything useful about the population it came from. For example, if we aim to understand the reproductive characteristics of our favourite study organism, but we only sample older individuals, it will be impossible to generalise our findings if reproductive performance changes with age.

The study of how to generate useful samples from a population is an important part of statistics. It falls under the banners of experimental design and sampling theory. These are large, technical topics, and it is well beyond the scope of this introductory book to study them in any great deal. We will touch on the more important practical aspects, particularly in the [Principles of experimental design] chapter.

Step 6: Estimate the population parameter(s)

Once we have a representative sample from a population we can calculate something called a point estimate of the population parameter. Remember, the population parameter is always unknown—that’s why we collect samples. A point estimate is simply a number that represents our best guess at the true value of the parameter. For example, if we are interested in a population mean, then the obvious point estimate to use is the mean of the sample (i.e. ‘the average’ we learn how to calculate in school).

People often say ‘estimate’ instead of ‘point estimate’, for the simple reason that saying or writing ‘point estimate’ all the time soon becomes tedious. We use both terms in this book.

Step 7: Quantify the uncertainty of estimate(s)

A point estimate is useless on its own. Why? Because estimates are always derived from a limited sample of the wider population. Even if we’re very careful about how we sample a population, and collect a really big sample, there is no way to guarantee that the composition of the sample exactly matches the population. This means any point estimate that we derive from a sample will always be imperfect, in that it won’t exactly match the true population value. There is always uncertainty associated with an estimate of a population parameter. What can we do about this? We have to find a way to quantify that uncertainty. This bit of the process can be tricky to understand, so we’ll spend a fair bit of time thinking about it in the [Sampling error] chapter.

Step 8: Answer the question!

Once we have point estimates and measures of uncertainty we’re finally in the position to start answering questions. We have to go about this carefully.

Imagine that we want to answer a seemingly simple question, e.g. “Are there more than 200 tonnes of carbon per hectare stored in the peatland of the Peak District?” We might sample a number of sites, measure the stored carbon at each of these, and then calculate the mean of these measurements. What should we conclude if the sample mean is 210 t h-1? We can’t say much until we have a sense of how reliable that mean is likely to be. To answer our question, we have to know how to assess whether or not the difference we observe (210 - 200 = 10) was just a fluke.

The tools we’ll learn about in this book are designed to answer a range of different kinds of scientific question. Nonetheless, they all boil down to the same basic question: Is the pattern I see ‘real’, or is it instead likely to be a result of chance variation? To tackle this, we combine point estimates and measures of uncertainty in various ways. Statistical software like R will do the hard work for us, but we still just have to learn how to interpret the results it gives us.

5.3 A simple example

The best way to get a sense of how all this fits together is by working through an example. We’ll finish this chapter by introducing a very simple example which we’ll use again in later chapters. We’re going to work through steps 1-6 here. The final two steps are sufficiently challenging that they need their own chapters.

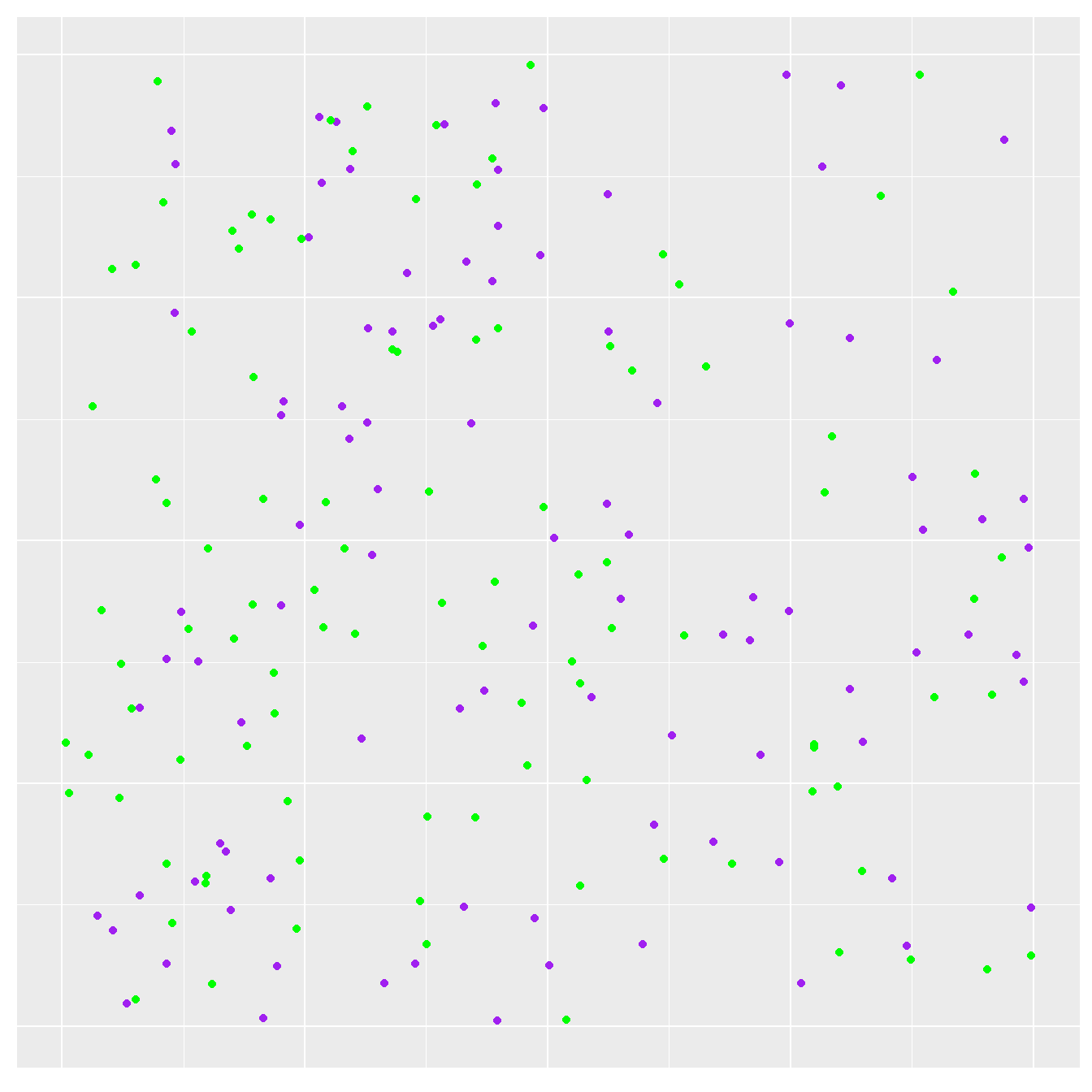

Imagine that we are working on a plant species that is phenotypically polymorphic. There are two different ‘morphs’, a purple morph and a green morph. We can depict this situation visually with a map showing where purple and green plants are located on a hypothetical landscape:

Figure 5.1: Stylised landscape showing a population of purple and green plants

These idealised data were generated using a simulation in R. Let’s proceed as though this were a real situation…

Step 1: Refine your questions, hypotheses and predictions

Imagine we had previously studied a different population that exhibits the same polymorphism. We’re fairly sure both populations were once connected, but habitat loss over the last few decades has significantly reduced the connectance between them. Our studies with the neighbouring population have shown:

The colour polymorphism is controlled by a single gene with two alleles: a recessive mutant allele (‘P’) confers the purple colour, and the dominant wild-type allele (‘G’) makes plants green. Genetic studies have shown that the two alleles are present in a ratio of about 1:1 in the neighbouring population.

There seems to be no observable fitness difference between the two morphs in the neighbouring population. What’s more, about 25% of plants are purple. This suggests that the two alleles are in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. These two observations indicate that there is no selection operating on the polymorphism.

Things are different in the new study population. The purple morph seems to be about as common as the green morph, and some preliminary research indicates that purple plants seem to produce more seeds than green plants. Our hypothesis is, therefore, that purple plants have a selective advantage in the new study population. The corresponding prediction is that the frequency of the purple morph will be greater than 25% in the new study population, as selection is driving the ‘P’ allele to fixation.

(This isn’t the strongest test of our hypothesis, by the way. Really, we need to study allele and genotype frequencies, not just phenotypes. Sadly, since the Brexit vote, the government has pulled the research funding for genetic research on plant polymorphism, so this is the best we can do.)

Step 2: Decide which population is important

Our situation is made up, so consideration of the statistical population is a little artificial. In the real world, we would consider various factors, such as whether or not we can study the whole population or must restrict ourselves to one sub-population. Working at a large scale should produce a more general result, but it could also present a significant logistical challenge.

Step 3: Decide which variables to study

This step is easy in this example. We could measure all kinds of different attributes of our plants—biomass, height, seed production, etc—but to study the polymorphism, we only need to collect information about the colour of different individuals. This means we are going to be working with a nominal variable that takes two values: ‘purple’ or ‘green’.

Step 4: Decide which population parameters are relevant

The prediction we want to test is about the purple morph frequency, or equivalently, the percentage, or proportion, of purple plants. Therefore, the relevant population parameter is the frequency of purple morphs in the wider population. We need to collect data that would allow us learn about this unknown quantity.

Step 5: Gather a representative sample

A representative sample here is one in which every individual on the landscape has the same probability of being sampled. This is what people really mean when they refer to a ‘random sample’. Gathering a random sample of organisms from across a landscape is surprisingly hard to do in reality. It is at least easy to do in a simulation. Let’s seen what happens if we sample 20 plants at random…

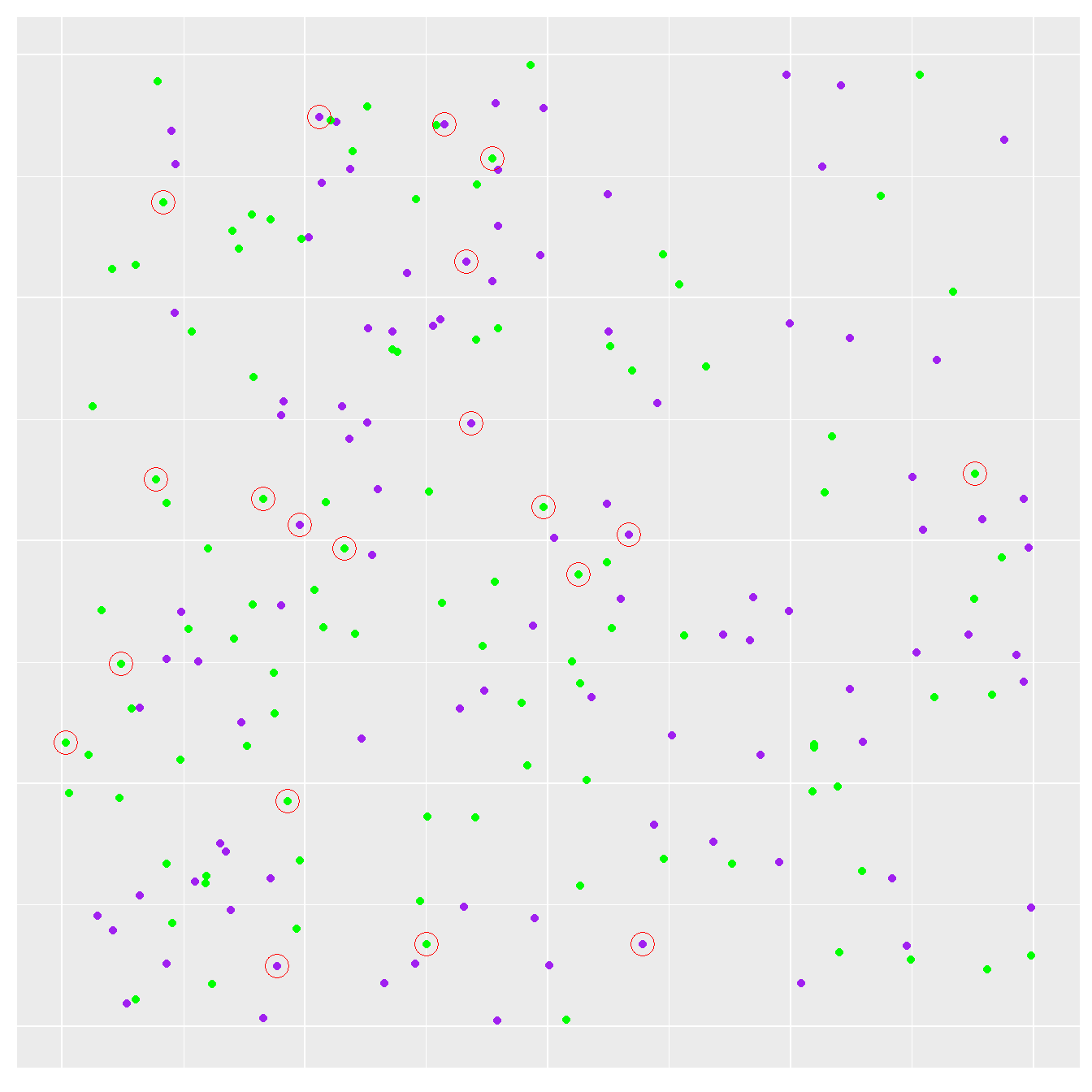

Figure 5.2: Sampling plants. Sampled plants are circled in red

The new plot shows the original population of plants, only this time we’ve circled the sampled individuals in red.

Step 6: Estimate the population parameter

Estimating a frequency from a sample is simple enough. We can express a frequency in different ways. We’ll use a percentage. We found 12 green plants and 8 purple plants in our sample, which means our point estimate of the purple morph frequency is 40%. This is certainly greater than 25%—the value of observed in the original population—but it isn’t that far off.

5.4 Now what?

Maybe the purple plants aren’t at a selective advantage after all? Or perhaps they are? We’ll need to use a statistical test of some kind to rigorously evaluate our prediction, but before we can do this, we need to learn a few more concepts. The first of these, sampling error, is the topic of the next chapter.