Chapter 6 Sampling error

In the previous chapter, we introduced the idea that a point estimate of a population parameter will always be imperfect, in that it won’t exactly reflect the true value of that parameter. This uncertainty is always present, so it’s not enough to have just estimated something. We have to know about the uncertainty of the estimate. We can use the machinery of statistics to quantify this uncertainty.

Once we have pinned down the uncertainty we can start to provide meaningful answers to our scientific questions. We will arrive at this ‘getting to the answer step’ in the next chapter. First we have to develop the uncertainty idea a bit more by considering things such as sampling error, sampling distributions and standard errors.

6.1 Sampling error

Let’s continue with the plant polymorphism example from the previous chapter. So far, we had taken one sample of 20 plants from our hypothetical population and found that the frequency of purple plants in that sample was 40%. This is a point estimate of purple plant frequency based on a random sample of 20 plants.

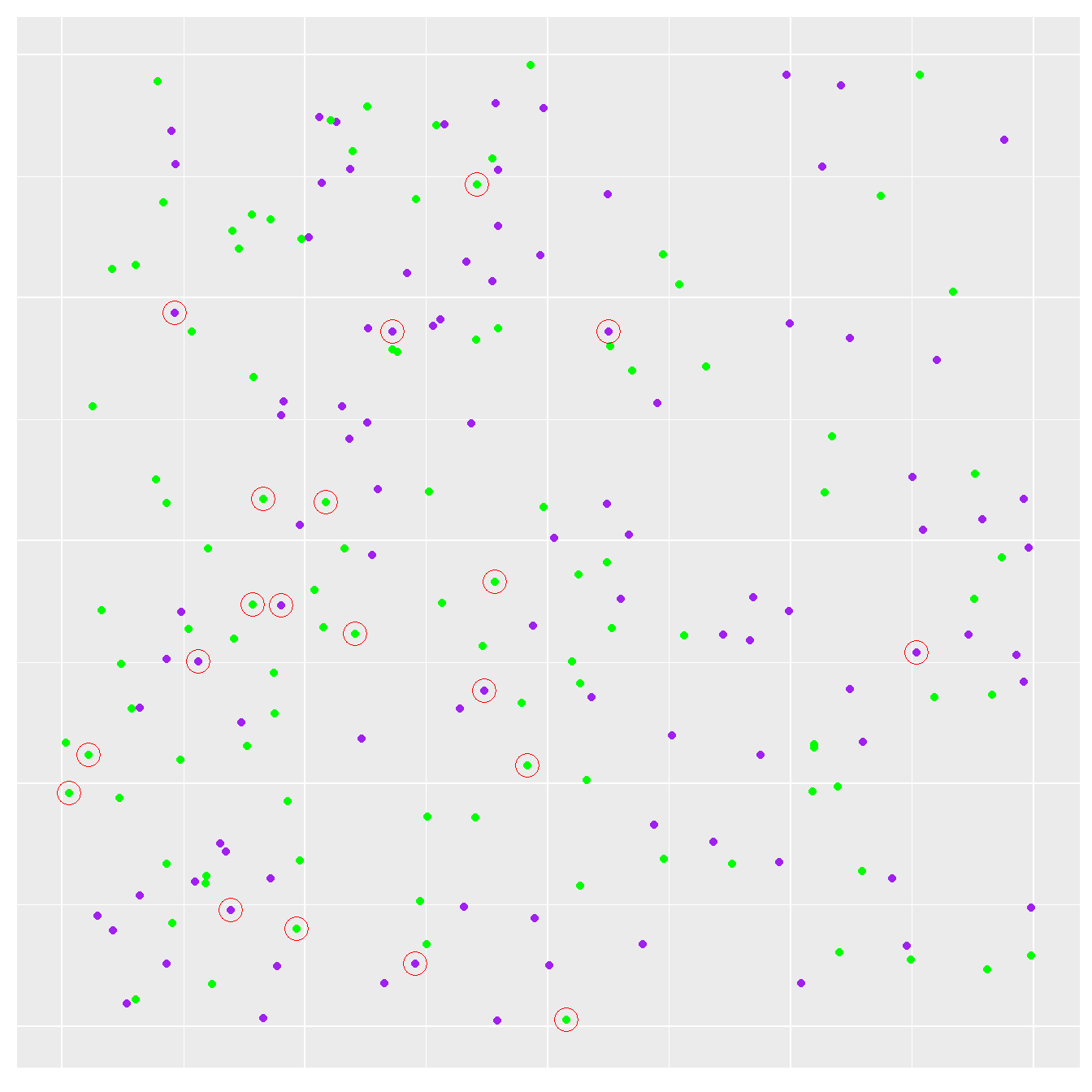

What happens if we repeat the same process, leading to a new, completely independent sample? Here’s a reminder of what the population looked like, along with a new sample highlighted with red circles:

Figure 6.1: Plants sampled on the second occasion

This time we ended up sampling 11 green plants and 9 purple plants, so our second estimate of the purple morph frequency is 45%. This is quite different from the first estimate. Notice that it is actually lower than that seen in the original study population. The hypothesis that the purple morph is more prevalent in the new study population is beginning to look a little shaky.

Nothing about the study population changed between the first and second sample. What’s more, we used a completely reliable sampling scheme to generate these samples (trust us on that one). There was nothing biased or ‘incorrect’ about the way individuals were sampled—every individual had the same chance of being selected. The two different estimates of the purple morph frequency simply arise from chance variation in the selection process. This variation, which arises whenever we observe a sample instead of the whole population, has a special name. It is called the sampling error.

(Another name for sampling error is ‘sampling variation’. We’ll use both terms—‘sampling error’ and ‘sampling variation’—in this book because they are both widely used.)

Sampling error is the reason why we have to use statistics. Any estimate derived from a sample is affected by it. Sampling error is not really a property of any particular sample. The form of sampling error in any given problem is a consequence of the population distribution of the variables we’re studying, and the sampling method used to investigate the population. Let’s try to understand what all this means.

6.2 Sampling distributions

We can develop our simple simulation example to explore the consequences of sampling error. Rather than taking one sample at a time, we’ll simulate thousands of independent samples. The number of plants sampled (‘n’) will always be 20. Every sample will be drawn from the same population, i.e. the population parameter (purple morph frequency) will never change across samples. This means any variation we observe is due to nothing more than sampling error.

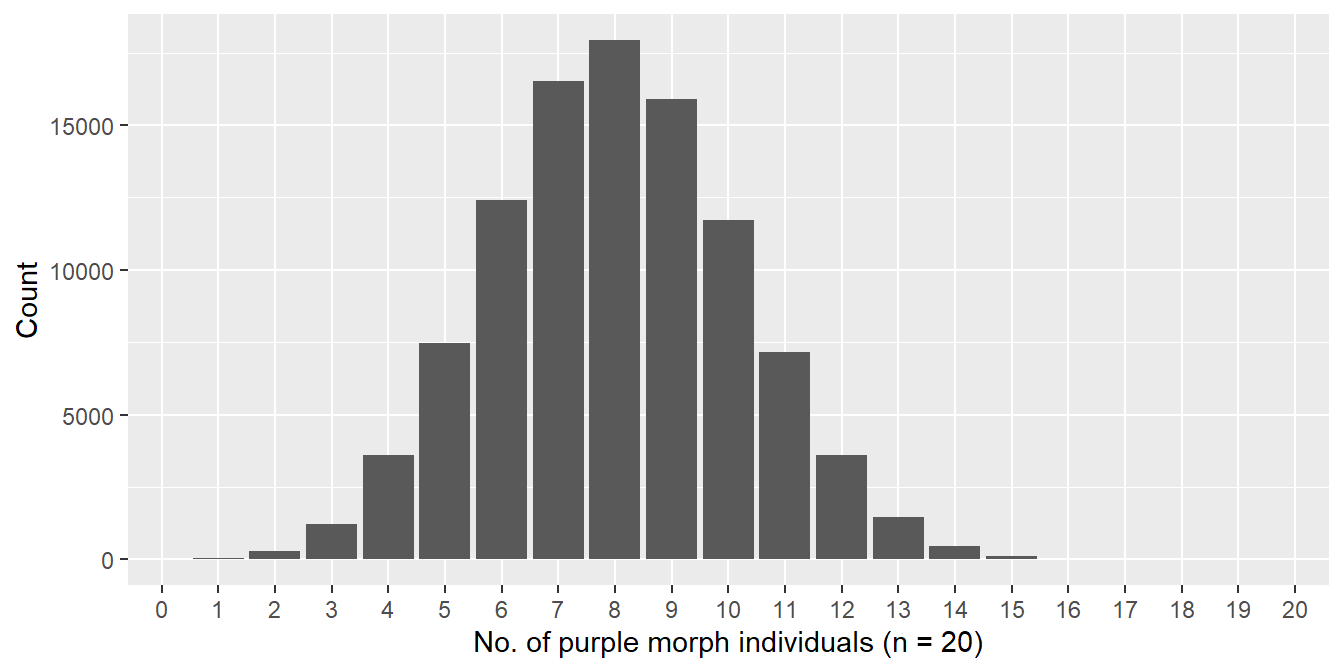

Here is a summary of one such repeated simulation exercise:

Figure 6.2: Distribution of number of purple morphs sampled (n = 20)

This bar plot summarises the result from 100000 samples. In each sample, we took 20 individuals from our hypothetical population and calculated the number of purple morphs found. The bar plot shows the number of times we found 0, 1, 2, 3, … purple individuals, all the way up to the maximum possible (20). We could have converted these numbers to frequencies, but here we’re just summarising the raw distribution of purple morph counts.

This kind of distribution has a special name. It is called a sampling distribution. The sampling distribution is the distribution we expect a particular estimate to follow. In order to work this out, we have to postulate values for the population parameters, and we have to know how the population was sampled. This can often be done using mathematical reasoning. Here, we used brute-force simulation to approximate the sampling distribution of purple morph counts that arises when we sample 20 individuals from our hypothetical population.

What does this particular sampling distribution show? It shows us the range of outcomes we can expect to observe when we repeat the same sampling process over and over again. The most common outcome is 8 purple morphs, which would yield an estimate of 8/20 = 40% for the purple morph frequency.

Although there is no way to know this without being told, a 40% purple morph frequency is actually the number used to simulate the original, hypothetical data set. So it turns out that the true value of the parameter we’re trying to learn about also happens to be the most common estimate we expect to see under repeated sampling. So now we know the answer to our question—the purple morph frequency is 40%. Of course, we have ‘cheated’ because we used information from 1000s of samples. In the real world we have to work with one sample.

The sampling distribution is the key to ‘doing statistics’. Look at the spread (dispersion) of the sampling distribution. The range of outcomes is roughly 2 to 15, which corresponds to estimated frequencies of the purple morph in the range of 10-75% (we sampled 20 individuals). This tells us that when we sample only 20 individuals, the sampling error for a frequency estimate can be quite large.

The sampling distribution we summarised above is only relevant for the case where 20 individuals are sampled, and the frequency of purple plants in the population is 40%. If we change either of those two things we end up with a different sampling distribution. That’s what was meant by, “The form of sampling error in any given problem is a consequence of the population distribution of the variable(s) we’re studying, and the sampling method used to investigate this.”

Once we know how to calculate the sampling distribution for a particular problem, we can start to make statements about sampling error, to quantify uncertainty, and we can begin to address scientific questions. We don’t have to work any of this out for ourselves—statisticians have done the hard work for us.

6.3 The effect of sample size

One of the most important aspects of a sampling scheme is the sample size (often denoted ‘n’). This is the number of observations—individuals, objects, items, etc—in a sample. What happens when we change the sample size in our example? We’ll repeat the multiple sampling exercise, but this time using two different sample sizes. First we’ll use a sample size of 40 individuals, and then we’ll take a sample of 80 individuals. As before, we’ll take a total 100000 repeated samples from the population:

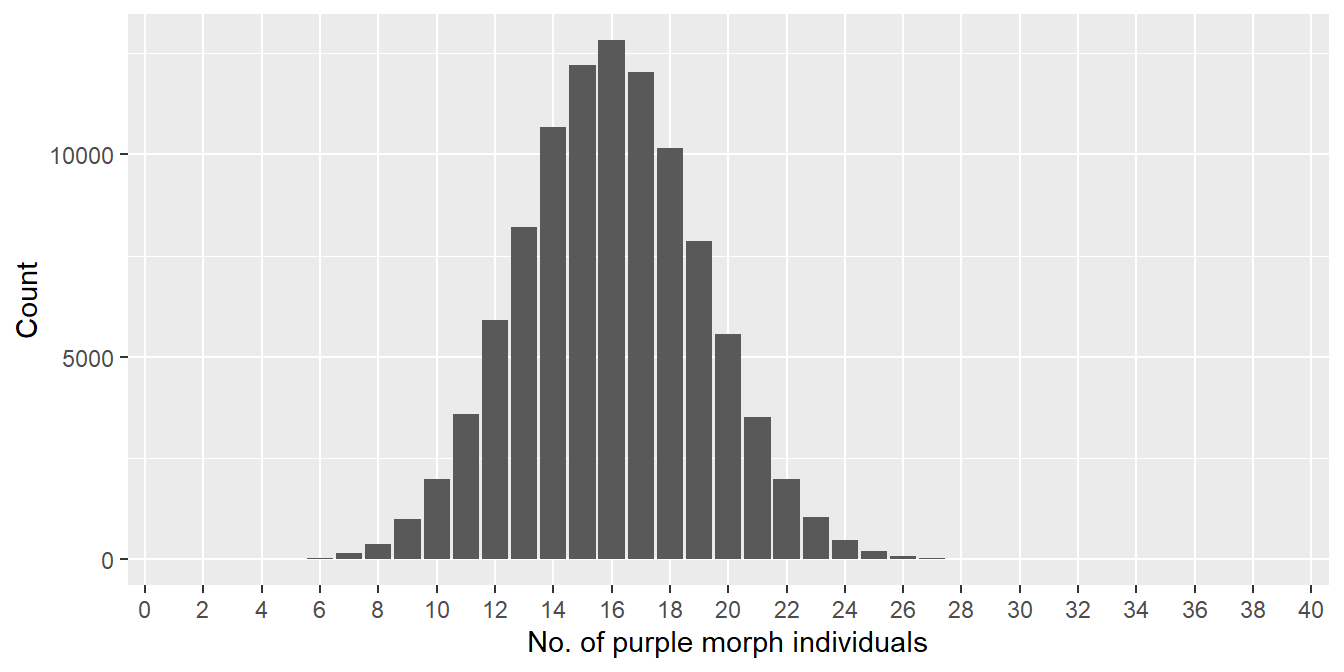

Figure 6.3: Distribution of number of purple morphs sampled (n = 40)

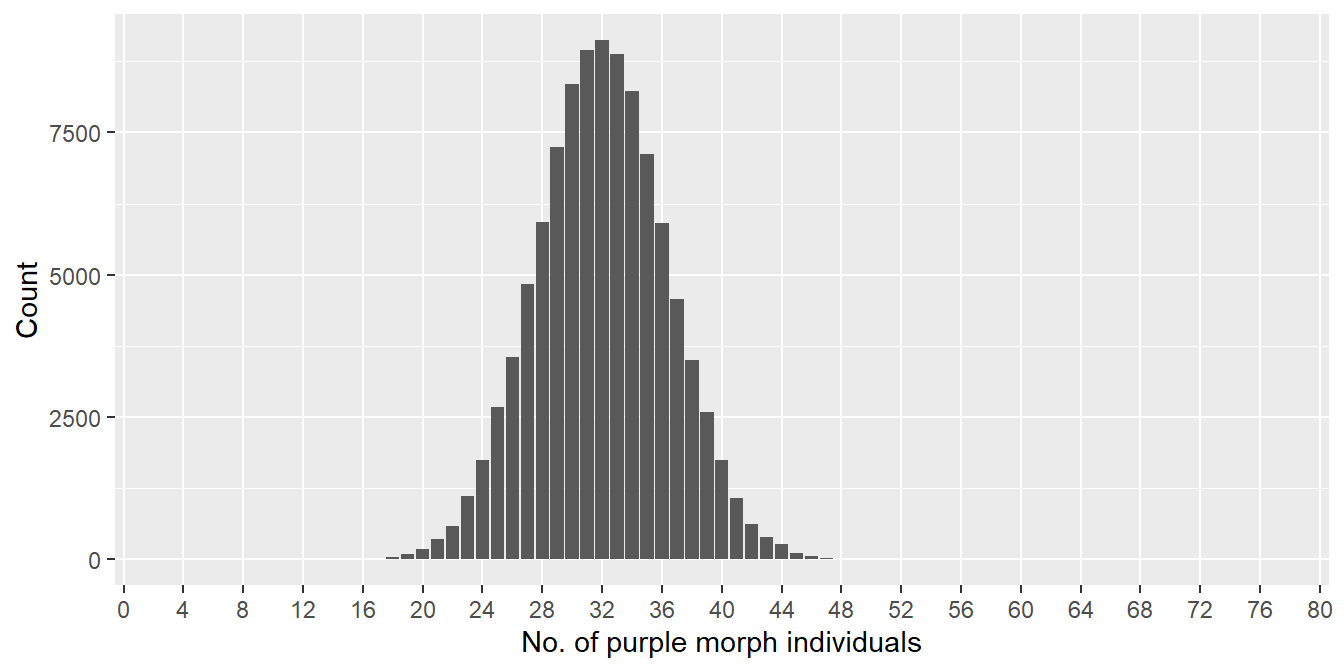

Figure 6.4: Distribution of number of purple morphs sampled (n = 80)

What do these plots tell us about the effect of changing sample size? Notice that we plotted each of them over the full range of possible outcomes, i.e. the x axis runs from 0-40 and 0-80, respectively, in the first and second plot. This allows us to compare the spread of each sampling distribution relative to the range of possible outcomes.

The range of outcomes in the first plot (n = 40) is roughly 6 to 26, which corresponds to estimated frequencies of the purple morph in the range of 15-65%. The range of outcomes in the second plot (n = 80) is roughly 16 to 48, which corresponds to estimated frequencies in the range of 20-60%. The implications of this not-so-rigorous assessment are clear. We reduce sampling error as we increase sample size. This makes intuitive sense: the composition of a large sample should more closely approximate that of the true population than a small sample.

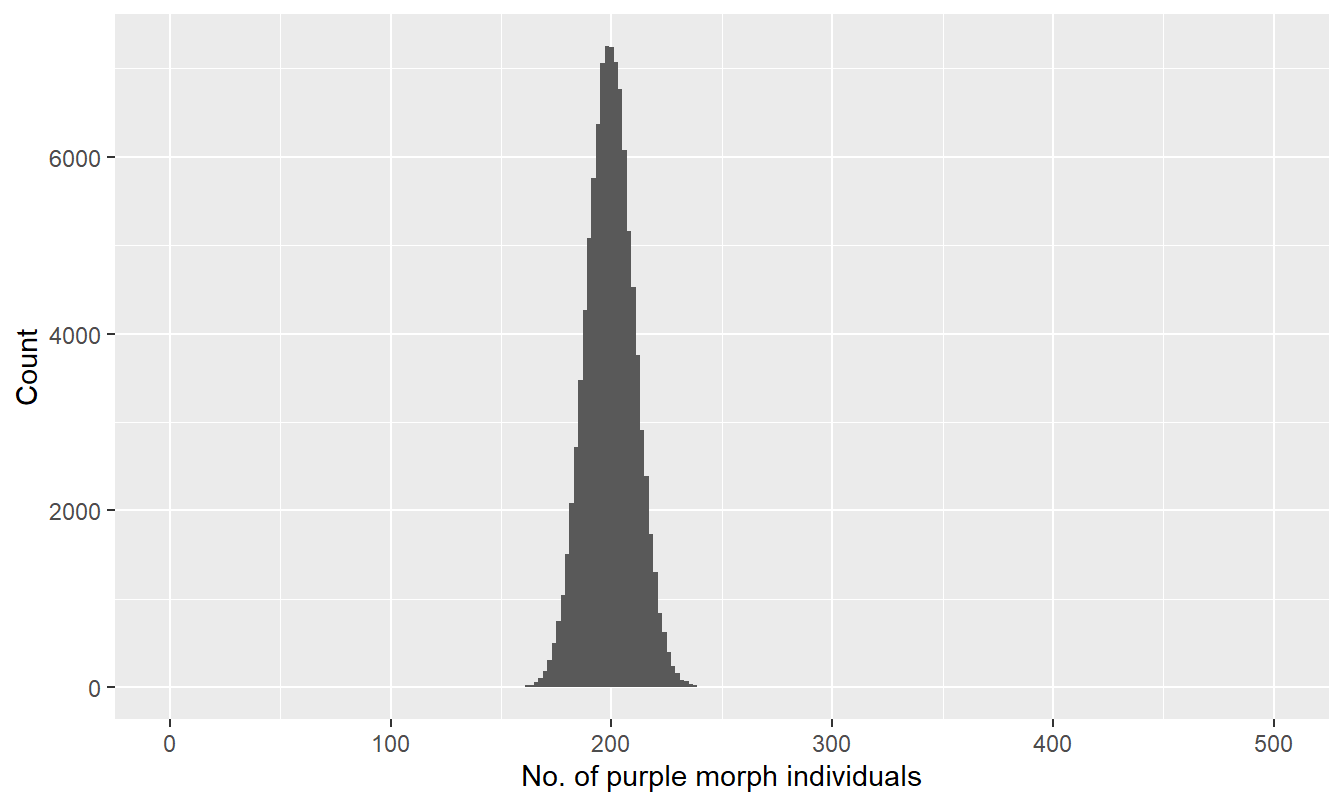

How much data do we need to collect to accurately estimate a frequency? Here is the approximate sampling distribution of the purple morph frequency estimate when we sample 500 individuals:

## Warning: Removed 2 rows containing missing values (geom_bar).

Figure 6.5: Distribution of number of purple morphs sampled (n = 500)

Now the range of outcomes is about 160 to 240, corresponding to purple morph frequencies in the 32-48% range. This is a big improvement over the smaller samples we just considered, but still, even with 500 individuals in a sample, we still expect quite a lot of uncertainty in our estimate. The take home message is that we need a lot of data to reduce sampling error.

6.4 The standard error

So far, we’ve not been very careful about how we quantify the spread of a sampling distribution—we’ve estimated the approximate range of purple morph counts by looking at histograms. This is fine for an investigation of general patterns, but to make rigorous comparisons, we really need a quantitative measure of sampling error variation. One such quantity is called the standard error.

The standard error is actually quite a simple idea, though its definition is a bit of mouthful: the standard error of an estimate is the standard deviation of its sampling distribution. Don’t worry, most people find the definition of the standard error confusing when they first encounter it. The key point is that it is a standard deviation, so it a measure of the spread, or dispersion, of a distribution. The distribution in the case of a standard error is the sampling distribution associated with some kind of estimate.

(It is common to use a shorthand abbreviations such “SE”, “S.E.”, “se” or “s.e.” in place of ‘standard error’ when referring to the standard error in text.)

We can use R to calculate the expected standard error of an estimate of purple morph frequency. In order to do this we have to specify the value of the population frequency, and we have to decide what sample size to use. Let’s find the expected standard error when the purple morph frequency is 40% and the sample size is 80.

First, we set up the simulation by assigning values to different variables to control what the simulation does:

The value of purple_prob is the probability a plant will be purple (0.4: R doesn’t like percentages), the value of sample_size is the sample size for each sample, and the value of n_samples is the number of independent samples we’ll take. That’s simple enough. The next bit requires a bit more knowledge of R and probability theory:

raw_samples <- rbinom(n = n_samples, size = sample_size, prob = purple_prob)

percent_samples <- 100 * raw_samples / sample_sizeThe details of the R code are not important here (a minimum of A-level statistics is needed to understand what the rbinom function is doing). We’re only showing the code to demonstrate that seemingly complex simulations are often easy to do in R.

The result is what matters. We simulated the percentage of purple morph individuals found in 100000 samples of 80 individuals, assuming the purple morph frequency is always 40%. The results are now stored the result in a vector called percent_samples. Here are its first 50 values:

## [1] 33.75 35.00 42.50 41.25 46.25 35.00 42.50 45.00 43.75 40.00 41.25 52.50

## [13] 43.75 38.75 38.75 47.50 42.50 40.00 43.75 42.50 36.25 42.50 43.75 43.75

## [25] 35.00 42.50 35.00 37.50 41.25 40.00 45.00 40.00 41.25 38.75 46.25 45.00

## [37] 31.25 40.00 47.50 42.50 37.50 41.25 31.25 45.00 32.50 36.25 40.00 37.50

## [49] 40.00 45.00These numbers are all part of the sampling distribution of morph frequency estimates. How to calculate the standard error? This is defined as the standard deviation of these numbers, which we can get with the sd function:

## [1] 5.494663Why is this useful? The standard error gives us a means to compare the variability we expect to see in different sampling distributions. When a sampling distribution is ‘well-behaved’, then roughly speaking, about 95% of estimates are expected to lie within a range of about four standard errors. Look at the second bar plot we produced, where the sample size was 80 and the purple morph frequency was 40%. What is the approximate range of simulated values? How close is this to \(4 \times 5.5\)? Those numbers are quite close.

In summary, the standard error gives us a way to quantify how much variability we expect to see in a sampling distribution. We said in the previous chapter ([Learning from data]) that a point estimate is useless without some kind of associated measure of uncertainty. A standard error is one such measure.

6.5 What is the point of all this?

Why have we just spent so much time looking at properties of repeated samples from a population? After all, when we collect data in the real world we’ll only have a single sample to work with. We can’t just keep collecting more and more data. We also don’t know anything about the population parameter of interest. This lack of knowledge is the reason for collecting the data in the first place! The short answer to this question is that before we can use frequentist statistics—our ultimate goal—we need to have a sense of…

how point estimates behave under repeated sampling (i.e. sampling distributions),

and how ‘sampling error’ and ‘standard error’ relate to sampling distributions.

Once we understand these links, we’re in a position to make sense of the techniques that underlie frequentist statistics. That’s what we’ll do in the next few chapters.